Climate Science Work Group Co-Chairs: Christian Braneon and Luis Ortiz

Anthropogenic climate change is fundamentally linked to the rapid increase in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions propelled by the Industrial Revolution and the European colonial systems that enabled it.

This NPCC4 chapter provides the latest assessment of the drivers and impacts of climate projections in New York City. It builds on earlier assessments and describes new methods to develop predictions of sea level rise, temperature change, and precipitation for the city. The chapter also presents updated “projections of record” for sea level rise, air temperature changes, extreme heat, precipitation, compound risks and extreme events to inform the City’s ongoing policy efforts.

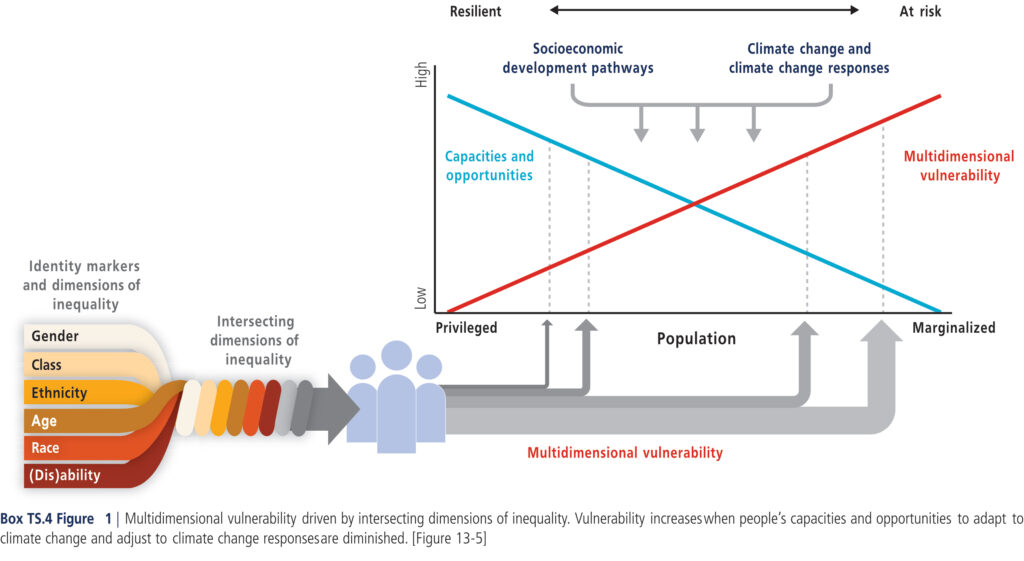

NPCC4’s focus on equity highlights that vulnerability to climate hazards and stressors is inequitably distributed in NYC. In response, this chapter emphasizes the equity implications of climate change adaptation.

The data show average annual air temperatures have increased over the last 70 years across the city. In addition, the daily nighttime temperature is increasing at a faster rate than daytime temperatures. The total number of hot days and nights is expected to increase, as is the frequency of heat waves. Total annual rainfall is also predicted to increase, though with less certainty than air temperature predictions, along with the number of extreme rainfall events. Sea level is also predicted to rise and potentially accelerate as the century progresses.

In addition to offering these projections, the chapter also describes how large-scale climate processes, along with local land and infrastructure characteristics, affect extreme heat in the city. Local drivers in New York City include urban infrastructure (e.g., streets, sidewalks, and buildings) and the natural environment (e.g., shrubs, trees, and grasses). Local and physical factors can lead to inequitable exposure to risks from extreme heat, including stronger urban heat islands. Considering different experiences of extreme heat across the city is important for developing an equitable strategy.

Lastly, the chapter discusses the implications of low probability extreme weather and climate change scenarios, known as “tail risks.” These tail risks can have significant consequences for cities (e.g., Hurricane Sandy), so it is important to consider their implications. The chapter discusses tail risks associated with rainfall, sea level rise, and tropical cyclones.

Photo Credit: University Neighborhood Housing Program Cool Roofs: Dana Ullman, UNHP, City of New York Mayor’s Office of Climate and Environmental Justice